Nike: the goddess of victory and shoes, apparently. When she isn’t brandishing a sword or rocking a sweet toga, Nike assumes the form of a multinational corporation that specializes in sports gear. Financially, the company has lived up to its name. In 2018 market research firm Statista ranked Nike as the top sports brand on Earth, with an estimated worth of $28 billion. Its products are everywhere and worn by every type of person: famous athletes, couch potatoes -– even babies wear Nike clothes, and babies can’t “just do” anything.

Some of the most successful MJs in history have done business with the company. Of course, there’s Michael Jordan with his coveted “Air” sneakers. Then there’s Olympic sprinter Michael Johnson, who wore custom-made gold Nike shoes at the 1996 Atlanta Games. However, not all is hunky-dory in Victory-ville. Nike has a bizarre and controversial history defined by violence, human rights violations, and incredibly ugly allegations. Just read it.

The mad shoe scientist

Every shoe becomes a running shoe if a bear’s chasing you, but if you’re running for exercise or a race, you can afford to be picky about footwear. During the 1950s, very few bears attended track meets, so track and field coach Bill Bowerman got really choosy about what athletes put on their feet. He thought all the existing sports shoes sucked because they were heavy and contained metal. Frustrated, Bowerman set about constructing lighter, more comfortable alternatives.

According to Nike’s official website, Bowerman consulted a cobbler to learn how the footwear sausage was made. And given how much experimenting he did, it wouldn’t be too surprising if he had made shoes out of actual sausages. Bowerman tested a wide range of materials, including kangaroo, deer, and fish skin.

Bowerman would eventually co-found Nike, where he continued trying out new ideas. While eating waffles one day, it dawned on him that designing shoe soles with “raised waffle-grid nubs” might create traction on diverse surfaces, eliminating the need for metal spikes. Eager to test his hypothesis, Bowerman stuck some urethane in a waffle iron and accidentally glued the thing shut. Ultimately, his mouth-watering concept succeeded, resulting in shoes that are perfect for walking, running, and breakfast.

Outraging Bull

Michael Jordan didn’t need special shoes to win games or bend gravity to his will. But a line of Nike sneakers would significantly impact his legacy. The first Air Jordans were created in 1984, MJ’s rookie year in the NBA. Controversy quickly ensued. Per The Atlantic, the NBA initially banned the sneakers, and Jordan would be accused of ignoring social issues while making a fortune on high-priced shoes that were incredibly popular in the black community.

Sometimes the sneakers were too popular. In 1990 Sports Illustrated reported on 15-year-old Michael Thomas, who was strangled to death in 1989 over a $115 pair of Air Jordans. It was part of a larger pattern of sneaker-related violence which has persisted for nearly 30 years. In 2017 a teen in Washington D.C. and a teen in Michigan were shot to death for their Air Jordans. In 2015 it was estimated that 1,200 people are killed over sneakers each year.

While Air Jordans obviously don’t account for all footwear-related homicides, people have criticized both Nike and Michael Jordan for marketing their shoes as must-have status symbols. Jordan has also been blasted for his silence and apparent indifference, but that’s kind of his M.O. When asked how he felt about Nike’s use of child labor back in 1996, His Airness basically shrugged and said, “I don’t know the complete situation. Why should I? I’m trying to do my job.”

Just do what exactly?

Long before Shia LaBeouf screamed “Just do it!” like he was commanding himself to pass a kidney stone, ad exec Dan Wieden (above) turned those words (minus the screaming) into an advertising masterpiece. It was 1988. Nike was still in its infancy and needed a unifying catchphrase for commercials. Wieden came up with the most generically bossy sentence in the English language, “just do it.” Nike co-founder Phil Knight scoffed at the suggestion, declaring, “We don’t need that sh*t.” But Wieden insisted that he was onto something. What did he see that Knight didn’t? Probably bullets.

In an interview with Dezeen, Wieden explained that Nike’s slogan was inspired by Gary Gilmore, a relentless criminal who robbed and killed two people in 1976. Gilmore was sentenced to death via firing squad and when asked if he had any last words, he either said, “Let’s do it” or “let’s do this.” Either way, Wieden was struck by the audacity of that response and thought a modified version of it would make a great slogan. He was right.

Death threats and dollars

Nike practically owns USA Track and Field. A partner since 1991, the sportswear titan is USATF’s biggest corporate backer and will supply athletic gear until 2040 as part of a deal worth between $400 million and $500 million. FloTrack determined that Nike-sponsored athletes accounted for 115 of the 200 individual medals won by USATF at the Olympics between 1996 and 2016. That translates into a lot of power, and as we all know, with great power comes great abuses of power.

Perhaps the most powerful figure in American track and field is John Capriotti, who serves as Nike’s global director of athletics. He’s the guy who allocates track-related sponsorship money and decides the outcomes of negotiations with sports agents. According to runner Will Leer, who was sponsored by Nike from 2013 to 2016, tales of Capriotti’s violence “are legend in track and field.”

For example, at a 2015 competition Leer witnessed the director threaten to murder the coach of an opposing team. According to a police report obtained by LetsRun.com, Coach Danny Mackey alleged that Capriotti grabbed, browbeat, and him in front of multiple eyewitnesses. The exact motive is unclear, but the Nike official accused Mackey of bringing him up at a meeting and referenced a doping scandal. The coach declined to press charges. Others who say they’ve been threatened by Capriotti have remained anonymous for fear that he would harm their careers.

The $35 checkmark

The Swoosh logo looks like a pointy letter J that fell over after getting blackout drunk. But if you stick it on a shoe it looks like dollar signs. However, when Nike’s founders first saw the design in 1971, they considered it unremarkable. That might sound ridiculous now, but hindsight is 20/20, or in Nike’s case $20 billion. In 1971 the company had very little money and wasn’t even called Nike until weeks after adopting the Swoosh. Before that it was Blue Ribbon Sports, which future shoe tycoons Bill Bowerman and Phil Knight had founded in 1964.

The Swoosh was created by graphic designer Carolyn Davidson, who did freelance work for Blue Ribbon Sports for $2 an hour. Speaking with the Oregonian, Davidson recalled that when she first presented the Swoosh, it was met with unenthusiastic silence. An underwhelmed Knight later remarked, “I don’t love it, but maybe it will grow on me.” However, the Blue Ribbon crew liked the curvy checkmark more than Davidson’s other ideas and purchased it for $35. As a thank-you for her contribution to the company, Nike later gave her several hundred shares of stock and a diamond ring. Davidson has said she felt “well compensated.”

How low can you logo?

A logo should grab your attention without mugging your eyeballs. Coming up with something charming and original is hard, though, so occasionally businesses just steal someone else’s idea and hope nobody notices. Even Nike, which boasts the world’s most famous checkmark, has been accused of creative shenanigans.

In 2018 Nike teamed up with the LA-based company Undefeated to launch a clothing line whose logo looked suspiciously like the crest of the U.S. Naval Academy. CNN reported that a promotional video for the clothes caused an online brouhaha. The USNA politely told Nike to quit the crap. Nike did, because when the Navy tells you to do something, you just do it.

In 2015 Dutch photographer Jacobus Rentmeester sued Nike for allegedly basing its iconic Jumpman logo on his work. As Reuters detailed, in 1984 Rentmeester took a snapshot of Michael Jordan making a ballet-inspired leap over a grassy knoll with an upraised basketball. Months later, Nike produced a similar photo set against the Chicago skyline. Three years later it used a silhouette of the second pose as the Jumpman logo. Despite the curious timing and visual parallels, Rentmeester lost in court.

Interestingly, in 2017 Nike complained when New England Patriots tight end Rob Gronkowski made a logo that closely resembled the Jumpman. Per ESPN, Gronkowski’s clothing company, Gronk Nation, attempted to trademark a silhouette of him in a wide-legged stance spiking a football.

The Oregon paper trail

The Oregon Project sounds like something you’d uncover at a CIA black site, but according to Nike, it helped America excel at distance running. The initiative started in 2001 when track coach Alberto Salazar (above) got sick of losing, something U.S. distance runners had been doing since the 1990s. With help from the biggest sports brand in the world, Salazar’s runners started setting national records and winning gold medals. All it took was recruiting younger athletes, “Nike technology and resources,” and possibly doping.

A joint investigation by ProPublica and the BBC revealed that at least 17 athletes and Oregon Project employees have claimed Alberto Salazar gave runners testosterone and prescription drugs with performance-enhancing side effects. To skirt detection he allegedly exploited a medical exemption in anti-doping restrictions. More than seven athletes accused Salazar of giving them unnecessary or unprescribed medications. Among the substances mentioned was Cytomel, a thyroid hormone drug that can be lethal in large doses. A former science adviser for the Oregon Project said Salazar had his own son take testosterone to figure out what dosage would arouse suspicion.

Salazar maintained his innocence, and the paperwork seemed to back him up. However, in 2017 the Russian hacking group Fancy Bear leaked an incriminating report by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency. The agency found evidence of widespread prescription drug misuse and indications that Oregon Project medical records had been altered. Moreover, it noted a half-dozen cases where cheating seemed “highly likely.” Whatever! Just dope it.

Glassdoor and glass ceiling

In March 2018, the website Racked noticed a disturbing theme in Glassdoor reviews about Nike. Women who currently or previously worked at the company’s headquarters in Oregon described a “frat boy culture” where “jocks rule the school” and bullying is commonplace. Women were underpaid compared to men, passed up for promotions, and told to sit and shut up during meetings.

This all came amid an “exodus,” according to the New York Times, of “top male executives” in response to an alarming internal survey. Women respondents highlighted instances of verbal abuse, sexual harassment, and generally crass mistreatment by male staff. One woman said Nike failed to act when she reported her supervisor for calling her a “stupid b*tch” and throwing his keys at her. By May 2018, at least 11 executives had gotten the boot or walked away from the company.

More horrifying allegations surfaced when two women sued Nike for sexual harassment. As detailed by the New York Post, the former employees alleged that a male exec sent nude photos of himself to female coworkers (including one of the plaintiffs), reached under employees’ skirts, and propositioned women at work. Some of these transgressions reportedly happened in front of other high-ranking men who did nothing to stop them.

Do you want a Beatles lawsuit?

In 2017 Rolling Stone revisited a watershed moment in advertising. Thirty years prior, Nike ran a TV commercial titled “Air Revolution,” which featured Michael Jordan, the emotionally explosive John McEnroe, and a bunch of people being physically fit. In an unprecedented move, Nike used the original recording of the Beatles song “Revolution” to set the tone.

Up to that point, when a company wanted to use an iconic song to manipulate consumers, it played a cover. Nike had broken with years of tradition and, perhaps more remarkably, did so by pissing off one of the most beloved bands of all time. The Beatles weren’t in the business of selling “sneakers or panty hose,” according to their lawyers, so the group sued.

In fairness to Nike, the Beatles didn’t actually own the publishing rights to “Revolution”; Michael Jackson had bought them. Moreover, the record label EMI-Capitol owned the band’s recordings. UPI reported that Nike paid Jackson and EMI-Capitol $250,000 apiece for the privilege of infuriating rock legends. In fact, the company was technically allowed to keep using “Revolution” until 1989. However, it relented a year early, citing “business reasons unrelated to the Beatles lawsuit.”

Bad habits die hard

Treating workers humanely can get pretty expensive, so a lot of employers don’t bother unless someone forces them to. That has certainly been the case for Nike. Overseas sweatshops have played an essential role in its operations since the 1970s, per Encyclopedia.com. People complained, but it wasn’t enough to hurt the bottom line. Then 1996 happened.

As The Guardian recounted, an incendiary photo surfaced of a Pakistani child sewing a Nike football. 1997 brought another black eye when the public discovered that workers at a Nike-contracted sweatshop in Vietnam “were being exposed to toxic fumes at up to 177 times the Vietnamese legal limit.” Overseas employees also endured violence and humiliation and were coerced into working over 70 hours a week. Some laborers reportedly collapsed on the job. By 1998 Nike was reeling from anemic sales and disastrous PR. Forced to lay off employees due to slumping profits, the company promised to improve workplace conditions.

Since 2005 Nike has conducted annual audits of its overseas facilities and made progress reports, prompting Business Insider to write in 2013 that the corporation “solved its sweatshop problem.” Unfortunately, that may have been a hopeful overstatement. In 2017 the Worker Rights Consortium found that Nike employees in Vietnam “suffered wage theft and verbal abuse, and labored for hours in temperatures well over the legal limit of 90 degrees, to the point that they would collapse at their sewing machines.”

Come on, Nike, light my fire

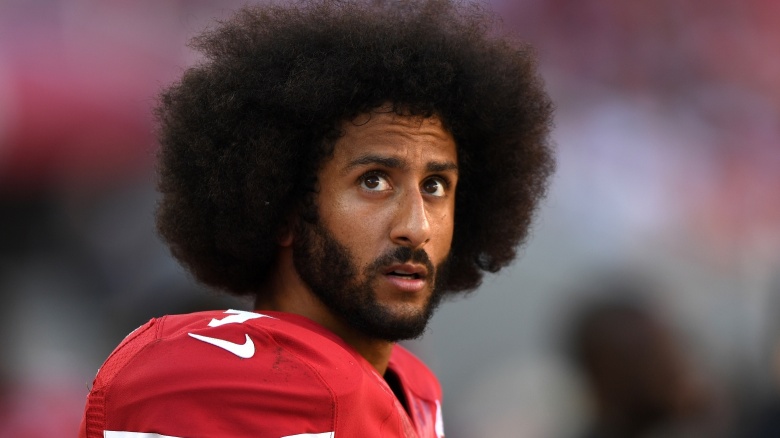

In 2016 NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick began kneeling during the National Anthem at football games to protest police violence against unarmed black males. The following season, no team in the league wanted to sign him. To Kaepernick’s supporters, he’s a hero. To his detractors, he’s a traitor who disrespected America and probably poaches bald eagles. To Nike, he’s lucrative.

In 2018 Nike ran an ad featuring Kaepernick and the text: “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.” People who believed Kaepernick’s knee committed treason decided to sacrifice all their Nike gear and filmed themselves burning shoes and mutilating socks.

Obviously, people are free to turn their footwear into firewood, and they’re free to buy Swoosh-emblazoned shoes as a nod to Kaepernick like Jim Carrey did. But here’s the thing: Corporations tend to be amoral. Their ethics depend on their profits, and their profits depend heavily on their image. That’s why Nike’s logo isn’t a sweatshop worker shedding tears made of dollar signs. It just so happens that the company likes to project social awareness.

As Adweek pointed out, Nike ads have long touched on politically charged subjects, including gender equality and ageism. A 1995 commercial starred an openly gay runner with HIV. Kaepernick was part of a clever calculation that increased brand loyalty among Nike’s main consumers, millennials. In fact, sales jumped and the company’s stocks hit an all-time high.